Beauford Delaney:

A Study in PortraitureCURATOR: MAIJA BRENNAN

Scroll over or click on the images in this exhibition

to find credits and descriptions.

Introduction

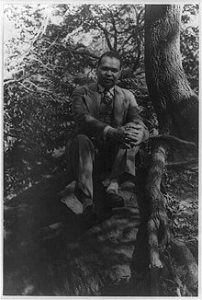

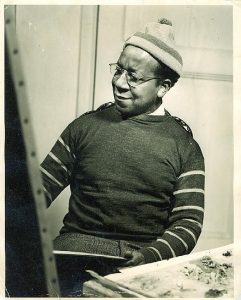

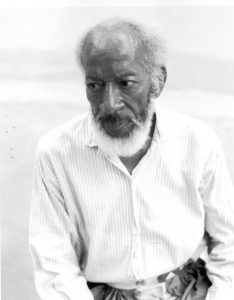

Beauford Delaney is an anomaly. Often linked to the Harlem Renaissance, other times to the Abstract Expressionist movement, he was once described by his close friend, James Baldwin, as a “cross between Brer Rabbit and St. Francis of Assisi.”

Delaney’s identity checked off a wide array of boxes; he was a gay, African-American man from Knoxville, Tennessee who lived through both World Wars and a multitude of tumultuous upheavals in many different forms. Despite being deeply conscious of the political, social and cultural repercussions he dealt with as a result of these intersecting identities, his art never reflected his thoughts or concerns on the topics too explicitly – either in the United States or in Paris, where he lived for over 20 years and where he eventually died in 1979. Because of this, his work has continued to astound and perplex art historians and critics alike who look to assign him a specific role in the canon of art history.

Delaney was multifaceted in his personhood and in his works of art, never painting himself into any particular stereotype or artistic movement. He loved light and he loved people, and both can be considered the largest influences reflected in the vast collection of art he created throughout his lifetime. He evolved from a portraitist reminiscent of the Old Masters to a man inspired by modernists around the United States and Europe, making the color “yellow” and heavy paint synonymous with his artistic aesthetic. Delaney brought the same level of movement and energy to a painting no matter the subject, whether a portrait of Jean Genet or a canvas covered in abstract swirls and marks.

Artists as dedicated to their craft as Delaney oftentimes give the impression of being solitary, introverted creatures. This is not so in Delaney’s case – he was a man who would forego his last dollar or an afternoon he could have spent painting to listen to someone in need. In the foreword to one of the last gallery shows of his lifetime, Henry Miller described him as not just a friend, but the friend. He was someone “who will give themselves entirely to you.”

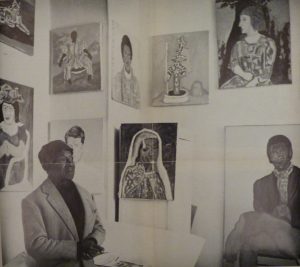

Through his portraiture, this exhibit explores the incredibly intimate and enriching relationships Delaney forged over the years, starting with his time at school in Boston, his transition to New York City where he spent 23 years, and finally the years following his move to Paris in 1953. The portraits will be viewed through the lens of how his evolving techniques, inspirations, and eventual deteriorating mental health influenced the realization of these works. The love that Beauford Delaney held for the people in his life is evident in the portraits on display through his playful and intriguing uses of paint and light.

A Nuanced Look …

A critique by Dr. Mary Campbell

Assistant Professor of Art History

University of Tennessee Knoxville

Is this the last day of my life? How does one tally the score? Love is all and that I give the world. Painting only now begins to explore all that I have felt and suffered.

Beauford Delaney (1901-1979) wrote these words in his journal on May 6th, 1962, a day after being readmitted to a medical clinic in the suburbs of Paris. The Knoxville-born artist indeed had suffered by this point—from poverty, from racism, from homophobia, and from the vicious hallucinations that necessitated his multiple stays various clinics and that would torment him until dementia left his mind mercifully blank. As Delaney himself insisted, however, he never abandoned his faith in love. “Our gods, the gods of love are very difficult,” he’d written to his close friend James Baldwin nearly a decade earlier, “but lovers can’t help being lovers.”

Although the art world largely forgot Delaney after his death, it’s finally beginning to remember the powerful work his aesthetic and personal commitment to the expansive generosity he labelled “love” produced. With her online exhibition Beauford Delaney: A Study in Portraiture, student-curator Maija Brennan traces this current through the artist’s life-long investment in portraiture. Beginning with the deftly executed charcoal portraits Delaney created during his Boston years before moving to the increasingly abstracted imagery he developed in New York and then Paris and ending with an exploration of his extended interest in self-portraiture, Brennan gives a nuanced look at this artist who rejected the hard distinctions so many of his contemporaries drew between the categories “figurative” and “abstract.” In the process, she provides a concise overview of Delaney’s artistic trajectory at a moment when critics and scholars are still working to reassemble his story.

Particularly useful on this front is the timeline Brennan includes at the beginning of her exhibition. Stretching from Delaney’s birth in 1901 to the long-overdue laying of his tombstone in 2010, this timeline visualizes key moments from the artist’s life by combining his own works with contemporaneous photographs, exhibition announcements, and Brennan’s elegant explanatory text. For those interested in Delaney’s development from an East Tennessee preacher’s son to a sophisticated, expatriate artist, this portion of the exposition is a jewel. Like Brennan’s exhibition in general, it provides a clear point of introduction to an undervalued artist who, in the words of the New York Times, is finally “return[ing] to the scene.”

Life in Knoxville

Delia Delaney instilled in Beauford an artistic disposition and a love for gospel music. His drive for his art and career can be traced to John Samuel Delaney, who was committed to his religion and his work despite numerous offsets and periods of poverty. The eighth of ten children (of which only four survived to adulthood), Beauford loved his siblings and his family fiercely, and the death of his brothers and sisters affected him deeply his entire life.

Although difficult at times, life in Knoxville for the Delaneys was relatively tranquil and family-centric. The artistic talents of Beauford and his brother, Joe, were nurtured by their mother, who would have them illustrate their Sunday School lessons.

In 1916, fifteen-year old Beauford was introduced to Lloyd Branson, a local celebrity. Branson was a painter who depicted Knoxville’s history, mainly focusing on the Confederacy and his patriotism. Despite his preferred subject matter, Branson took Beauford on as an apprentice, mentoring him in the visual arts and eventually funding his move to Boston.

As his first art teacher, Branson taught Beauford the importance of light in paintings, saying that the interaction of light with its subject is what made for an interesting and noteworthy work of art.Though Beauford only returned to Knoxville a handful of times after he left his hometown, he reflected fondly on his upbringing in his journals and with his close friends. Growing up in the South was something Beauford was always proud of, and it shaped the artist he would one day become.

The Boston Years

Beauford left Knoxville for Boston in September of 1923, scared and uncertain of the future that awaited him when he arrived on the East Coast. Encouraged by Lloyd Branson with both financial and moral support, his move was fueled by the desire to nurture his artistic talents and future career in a city more conducive to his needs.

Traveling to a different region of the United States, albeit it being the same country, can provide the same amount of culture shock as voyaging abroad, and Beauford found Boston overwhelming at first. Though the pace of life differed greatly from what he was used to back home in Knoxville, he quickly went about establishing connections that would propel him forward in his life and artistic career. With a letter of introduction provided to him by Branson, Beauford created his first important relationship, and found housing, with Mr. and Mrs Bryant – relatives of the poet William Cullen Bryant. In Amazing Grace: A Life of Beauford Delaney, biographer David Leeming cites the two as abolitionists and women’s rights activists who played imperative roles in Beauford’s sociopolitical education during these formative years. Beauford spent much of his time in Boston at Mrs. Bryant’s liberal salons for both intellectual and physical nourishment, as he often lacked funds for food. Among the cast of characters of the “1920s Boston Radicals” were William Shakespeare Sparrow, Butler Wilson, Archibald Grimké, William Monroe Trotter, and Countee Cullen. The people he met in these intensive and engaging environments were black lawyers, writers, NAACP board members, and prolific political activists; they represented his ability to gain access to elite worlds no matter where he went, and he established meaningful relationships with them all.In addition to forming his political consciousness in Boston, Beauford loved the city for the arts that were readily available to him, and of course, the schooling he was receiving. Through Branson, he was able to attend the Massachusetts Normal School, the South Boston School of Art, and the Copley Society. He frequented the Trinity Church and the Boston Symphony; his thirst for music was satiated at their concerts. He reveled in the history that was teeming in every corner, frequently visiting the Boston Commons and the dozens of monuments that littered the city.

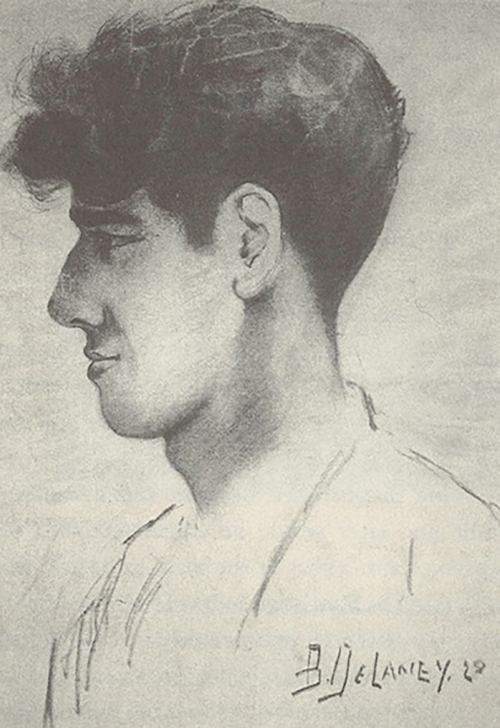

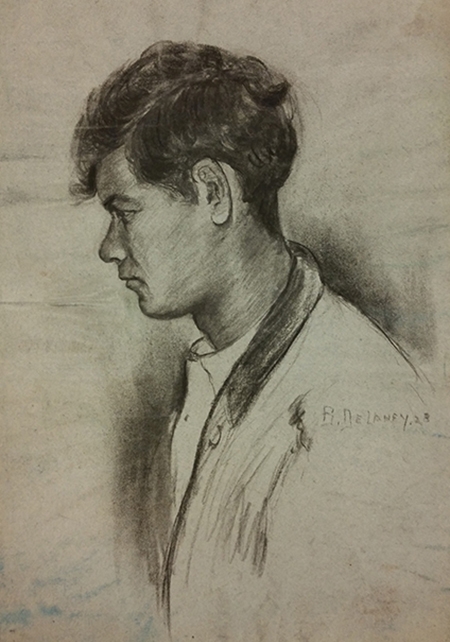

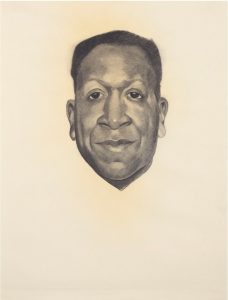

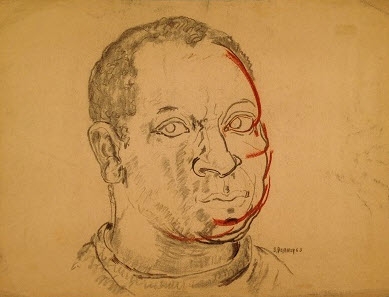

His favorite place though, was the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. He loved and greatly admired the traditional and representational paintings found there due to the classical training he was undergoing.Although there are few works of art from Beauford’s Boston years that are readily available, those that are available demonstrate the portraiture skills he gained from his classical instruction. Viewers are able to see the beginning stages of his evolution as a portraitist, when his main concern was to realistically render his subjects. Boston also provided access to the works of artists who would become his biggest influences: Claude Monet and John Singer Sargent. Beauford was in awe of the relationships they created with light and how it became the main subject of their paintings. He would take this with him everywhere he went and with every painting he created after Boston.

BOSTON PORTRAITS

The New York Years

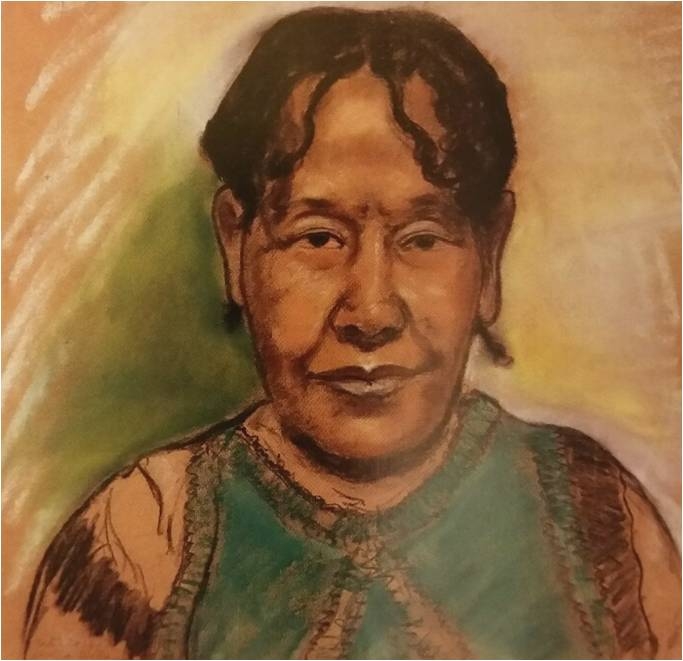

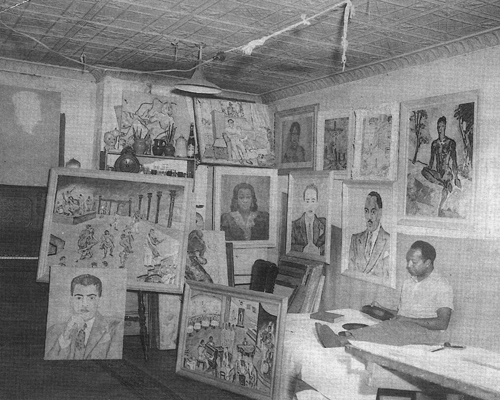

To start gaining money and a following, Beauford began drawing portraits of the dancers and high-society people that passed through the doors of Billy Pierce’s Dancing School. These portraits were extensions of the ones done in Boston, as his clients were paying for his ability to render likeness, not for explorations in abstraction. It was with his acquaintances and friends in Harlem that he took more liberties with the portraits he created. After winning first place for his portrait of Billy Pierce in his first exhibition at the Whitney Studio Galleries, Beauford gained recognition from journalists and more opportunities to show his work.

Over the course of his New York years, Beauford wanted to distance himself from “Negro art” and the concept of the “Negro artist,” the box he had been placed in by art galleries and critics alike. He began exploring more and more the world of abstraction, befriending modernists like Stuart Davis and Willem de Kooning, who imparted onto him their personal beliefs and ideas surrounding modern art.

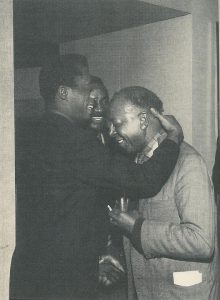

Portraiture remained a staple in Beauford’s practice though, and he drew and painted figures he simply admired, like W .E. B. DuBois and Ethel Waters, along with close friends, such as James Baldwin and Henry Miller.Beauford was part of two different worlds during the New York years, one of the white bohemians with whom he lived in close proximity in Greenwich Village, and the one of the black painters in Harlem with whom he worked and was friends. There were aspects of his life with which he struggled in secret: his homosexuality and the burden of frequent delusions and paranoia plagued him. He suppressed both, which resulted in bouts of depression.

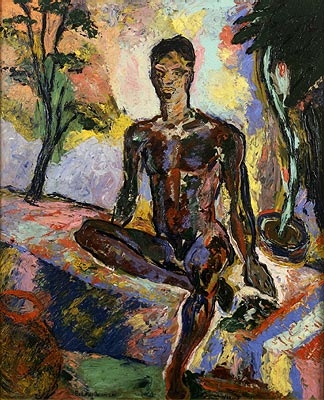

NEW YORK PORTRAITS

In both worlds however, Beauford developed meaningful friendships that would last for years into the future. The loving portraits he made of many of these friends are included in this exhibition. Beauford’s portraits are testaments to his adoration for close friends and family and his respect for everyone who passed through his life.

The Paris Years

It did not take long for Beauford once again to find his circle of people, friends that would remain by his side during the most trying episodes of the deterioration of his mental and physical health. His first night in Paris, restless and hungry, he stumbled into Le Dôme café on the corner of rue Delambre and boulevard du Montparnasse, a spot that would become one of his favorites for the remainder of his stay. Beauford thrived with a Parisian way of life, spending his days painting and sitting amongst groups of friends in cafés, philosophizing about life and art.

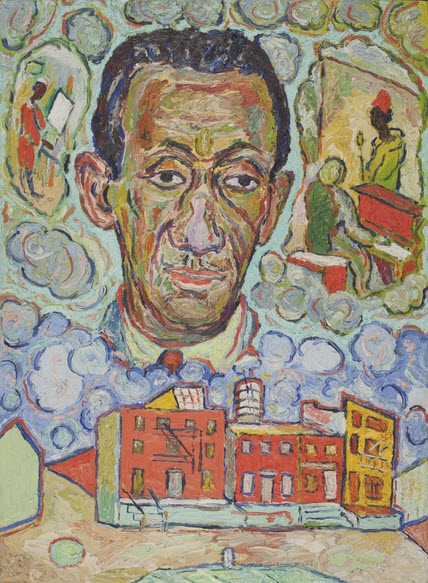

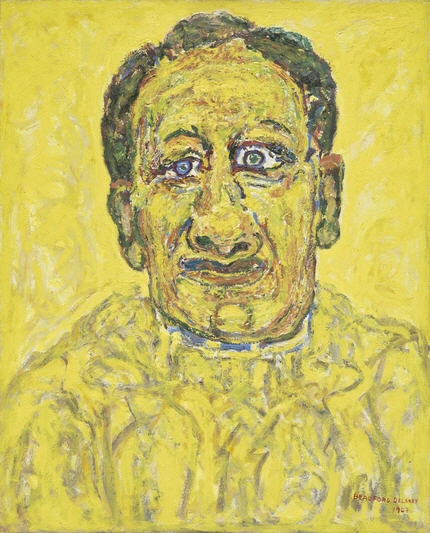

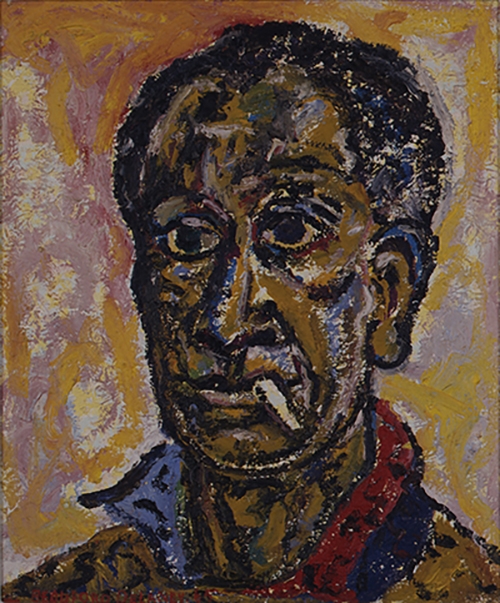

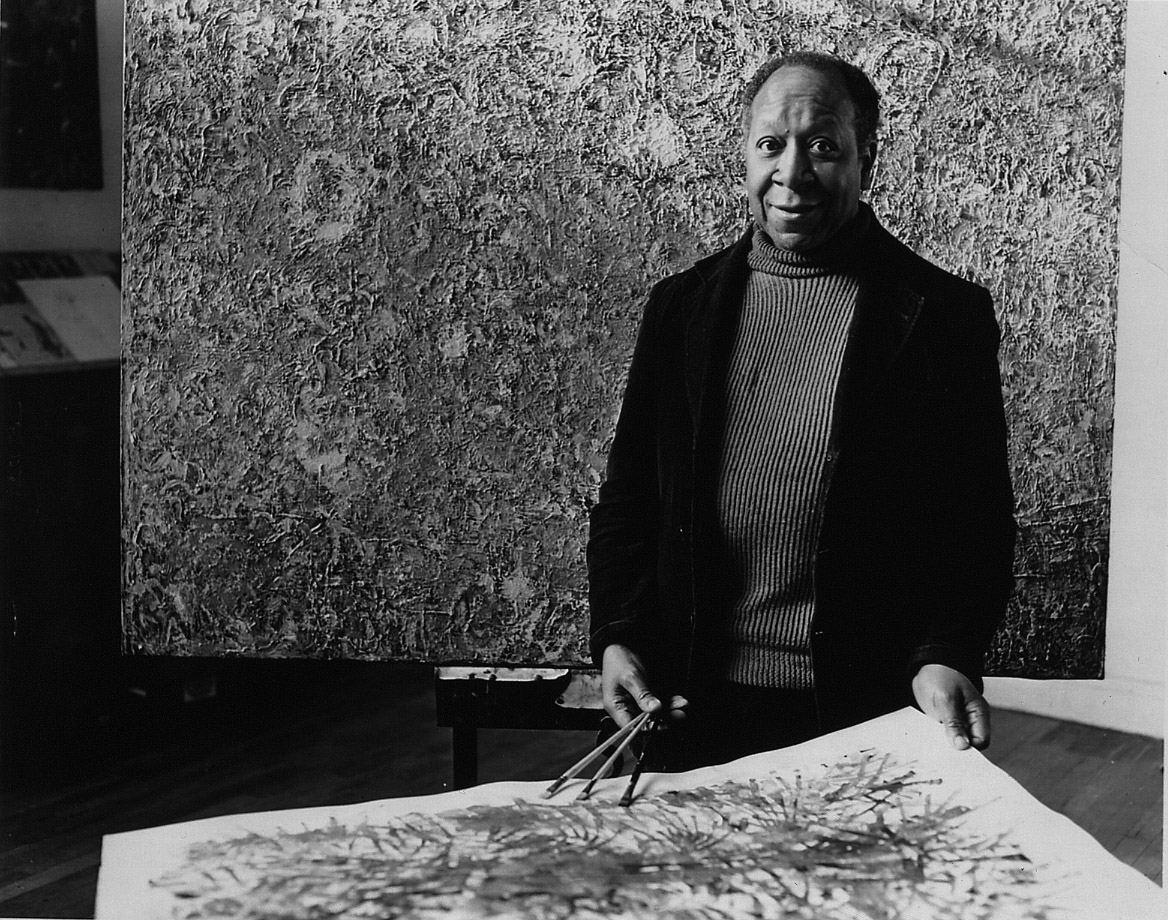

It was in Paris, with the religious light that it offered, where Beauford’s portraits and abstractions became more expressive and free in nature. From his Clamart apartment to his Vércingétorix atelier, his art took on many new dimensions – voyaging into nonrepresentational abstraction and experimenting with making light the focal point of every one of his paintings. He showed his work in galleries around Paris and Europe as he had done in New York, yet struggled financially. He survived through occasional sales and the generosity of friends. Despite his impoverished circumstances, he would give away most of his money to those he felt needed it more, a practice that had existed for Beauford since New York.PARIS PORTRAITS

Beauford loved his friends in Paris and the experiences he had with them. However, he experienced frequent periods of loneliness and depression. His paranoia worsened at the hands of eventual alcoholism, and by the 70s he needed close supervision. He continued creating his portraits and abstractions until he could no longer hold a paintbrush, which oftentimes was the only thing that could stave off the voices that tormented him mentally. His art from this time represents some of the best of his career, his portraits acting as love letters to not only the people that remained by his side, but also to paint and color for their ability to create such interesting juxtapositions of light and subject.

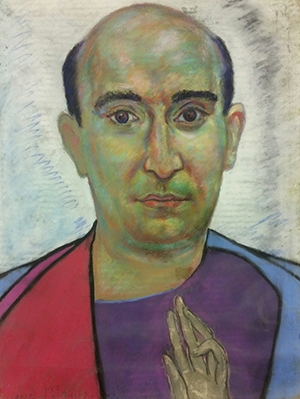

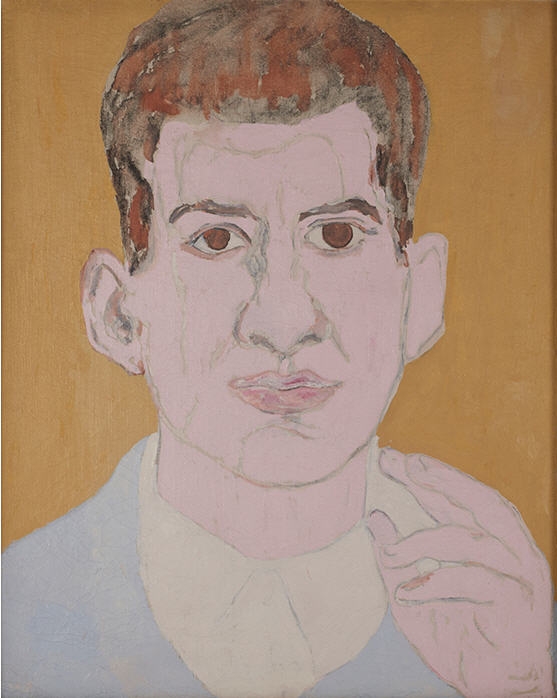

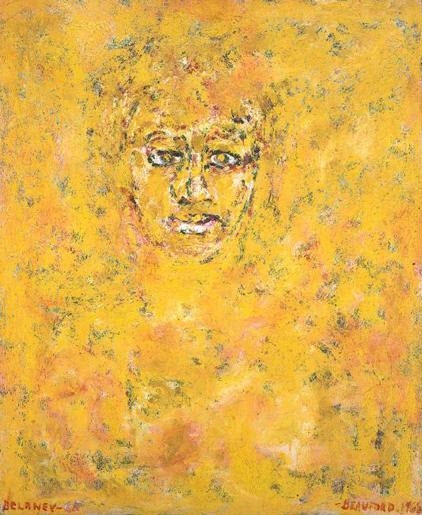

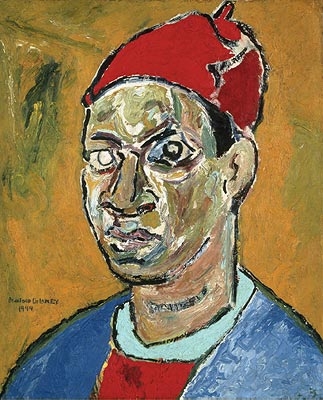

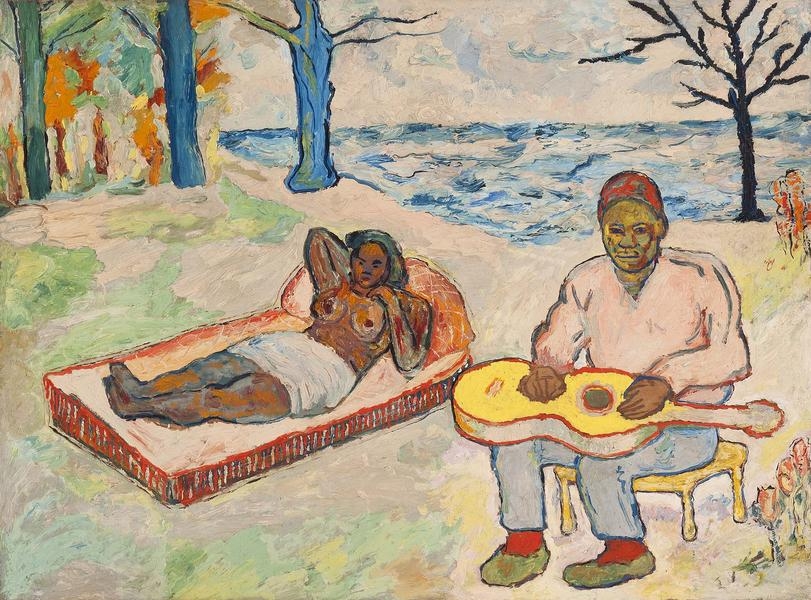

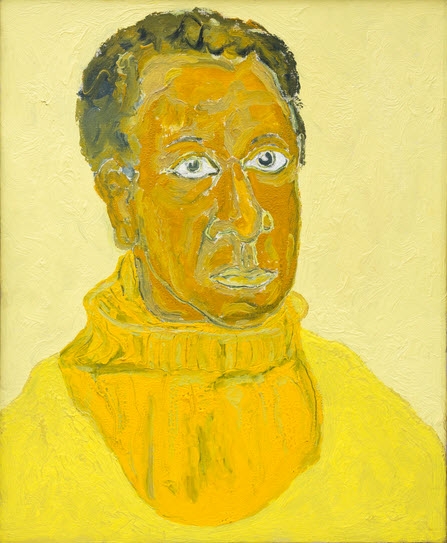

Self-portraits

Along with rendering all the important people in his life, Beauford practiced self-portraiture throughout his entire career. Being gay and African-American in the United States made feelings of acceptance by the greater society almost impossible, a fact aggravated by the voices and delusions that plagued him his entire life. As a result of this, it is easy to imagine that Beauford suffered from a highly unstable self-image and identity.

Many times artists reconcile this fact through their art, using it to explore aspects of themselves they may want to highlight or play down in the public eye. Beauford’s self-portraits are no different. In every self-portrait on display in this exhibit, he is staring out imploringly at the viewer, sometimes appearing inquisitive or distrustful. Each work begs questions of what he was thinking or going through at the time of its creation. The majority of Beauford’s self-portraits are frontal view paintings, with the focus always on his face and the feelings being emoted.In addition to being vehicles to portray inner truths about the artist, self-portraits are a way to practice new techniques in a certain medium. They are excellent for such exploration as the subject is always readily available and is one the artist knows well. Looking at the variety of Beauford’s self-portraits, we can see where he was experimenting with color and paint, or where he attempted new methods of visual storytelling and depictions of light.

Just like the portraits he created of others in his life, Beauford’s self-portraits illustrate his gorgeous artistic sensibilities, along with a deeper desire to depict inner thoughts and feelings externally.

SELF-PORTRAITS

Final Years

On March 26th, 1979, Beauford passed away. Due to financial obstacles, he could not be buried where his friend James Baldwin had hoped: Montparnasse Cemetery. Baldwin, so heartbroken at losing his mentor and “spiritual father” and plagued with myriad additional emotions and circumstances surrounding Beauford’s death, could not bring himself to attend the funeral. He was seriously ill, but he was also embarrassed that he was not able to have Beauford buried at Montparnasse. He would feel guilty for having missed the ceremony that marked Beauford’s transition.

Beauford lay in an unmarked pauper’s grave in the Parisian Cemetery of Thiais, virtually forgotten, until Dr. Monique Y. Wells discovered his burial place and set out to raise the funds for a tombstone that honored the man Beauford was. This was the first step in a renewed global interest in his life and career.

More than four decades after Beauford’s passing, increased awareness and scholarly research is being brought to the public’s attention regarding his artwork and prolific presence in the world. Numerous exhibitions of his art have been mounted in the United States and Europe, and with the Internet, new information and ways of looking at Beauford’s life in the context of art history are more accessible than ever.

James Baldwin once wrote about Beauford:Perhaps I should not say, flatly, what I believe – that he is a great painter – among the very greatest; but I do know that great art can only be created out of love, and that no greater lover has ever held a brush.

Beauford Delaney, summed up in one word, is “lover.” He was a lover of paint, of art, of light, and of the people that walked into his life at every turn. His portraits are reflections of all of that, and every viewer that encounters Beauford, no matter how, can learn something invaluable.

Works Cited

Sources for panel texts and timeline:

Introduction:

Leeming, David Adams. Amazing Grace: A Life of Beauford Delaney. Oxford Univ. Press, 1998.

Miller, Henry. “Henry Miller.” Beauford Delaney, Galerie Darthea Speyer, 1973.

Timeline – “Life in Knoxville,” “Boston Years,” “New York Years,” “Paris Years,” “Self-Portraits”:

Leeming, David Adams. Amazing Grace: A Life of Beauford Delaney. Oxford Univ. Press, 1998.

Final Years:

Baldwin, James. “Foreword.” Beauford Delaney: a Retrospective, Studio Museum in Harlem, 1978.

Leeming, David Adams. Amazing Grace: A Life of Beauford Delaney. Oxford Univ. Press, 1998.

Portrait citations:

Untitled (Portrait of a Young Man), 1928

“Hugh Tyler Collection.” Knox County Public Library Calvin M. McClung Digital Collection. http://cmdc.knoxlib.org/cdm/about/collection/p15136coll1. Accessed 18 August 2019.

Latto, Richard. “Turning the Other Cheek: Profile Direction in Self-Portraiture.” Empirical Studies of the Arts, vol. 14, no. 1, 1996, pp. 89–98., doi:10.2190/198m-911x-pr9g-u18e. Accessed 15 July 2019.

Leeming, David Adams. Amazing Grace: A Life of Beauford Delaney. Oxford Univ. Press, 1998.

Kirsch, Adam. “Vistas of Perfection.” Harvard Magazine, May-June 2009. https://harvardmagazine.com/2009/05/vistas-perfection. Accessed 15 August 2019.

Neely, Jack. “The Life of Knoxville Artist Beauford Delaney (1901-1979.” Knoxville Mercury, 18 February 2016. https://www.knoxmercury.com/2016/02/18/the-life-knoxville-artist-beauford-delaney-1901-1979/. Accessed 16 August 2019.

Untitled (Portrait of a Young Man), circa 1930-1935

Wells, Monique Y. “Sold!!! Two Delaneys at Swann Auction Galleries June 2014 African American Fine Art Auction.” Les Amis de Beauford Delaney, 14 June 2014, lesamisdebeauforddelaney.blogspot.com/2014/06/sold-two-delaneys-at-swann-auction.html. Accessed 11 July 2019.

Ethel Waters, 1940

Buja, Maureen. “Musicians and Artists: Ethel Waters and Beauford Delaney.” Musicians and Artists: Ethel Waters and Beauford Delaney, 26 June 2019, www.interlude.hk/front/musicians-artists-ethel-waters-beauford-delaney/. Accessed 24 June 2019.

Gaylord, 1944

Wells, Monique Y. “Where to Find Beauford’s Art: New England.” Les Amis de Beauford Delaney, 22 Oct. 2011, lesamisdebeauforddelaney.blogspot.com/2011/10/where-to-find-beaufords-art-new-england.html. Accessed 11 July 2019.

Dante Pavone as Christ, 1948

Leeming, David Adams. Amazing Grace: A Life of Beauford Delaney. Oxford Univ. Press, 1998.

Miller, Henry. The Amazing and Invariable Beauford Delaney. O. Baradinsky, 1978.

Portrait of a Young Man (Larry Calcagno), 1953

Leeming, David Adams. Amazing Grace: A Life of Beauford Delaney. Oxford Univ. Press, 1998.

Robinson, Joyce Henri. An Artistic Friendship: Beauford Delaney and Lawrence Calcagno:Palmer Museum of Art, the Pennsylvania State Univ., 2001.

Howard Swanson, 1967

Leeming, David Adams. Amazing Grace: A Life of Beauford Delaney. Oxford Univ. Press, 1998.

Wells, Monique Y. “Beauford and Howard Swanson.” Les Amis de Beauford Delaney, 9 Jan. 2016, lesamisdebeauforddelaney.blogspot.com/2016/01/beauford-and-howard-swanson.html. Accessed 12 July 2019.

Self-portrait, 1944

Biro, A., Moulin, Joëlle. “Henri Matisse.” L’autoportrait Au XXe Siècle: Dans La Peinture, Du Lendemain De La Grande Guerre Jusqu’à Nos Jours, by Joëlle Moulin, A. Biro, 1999, pp. 60–63.

Self-portrait, 1962

Reinfrank, Burt. “Beauford Describes Beauford: Beauford’s Tribute to Henry Miller.” Les Amis de Beauford Delaney, 8 Dec. 2010, lesamisdebeauforddelaney.blogspot.com/2010/12/beauford-describes-beauford-beaufords_08.html. Accessed 12 July 2019.

Self-portrait with Odalisque, 1944

Baldassarre, Antonio. “Being Engaged, Not Informed: French ‘Orientalists’ Revisited.” Music in Art, vol. 38, no. 1-2, 2013, pp. 63–87. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/musicinart.38.1-2.63. Accessed 3 July 2019.

Auto-portrait, 1965

Anderson, Jeffrey C. “The Byzantine Panel Portrait Before and After Iconoclasm,” The Sacred Image East and West, ed. Ousterhout and Brubaker, 25-44.

© 2019 Wells International Foundation. All rights reserved.