Katrina Stack is the Graduate Research Assistant for the Beauford Delaney Papers at the University of Tennessee Knoxville (UTK).

For the UTK Department of Geography and Sustainability’s 2025 GeoSym conference, she has organized a session entitled “Placing Beauford Delaney: Vision, Identity, and Legacy” to bring together diverse scholarly perspectives on Beauford’s rich and multifaceted body of work as well as explore the broader cultural, historical, and social contexts that shaped and were shaped by his art.

Stack was part of a group of University of Tennessee Libraries scholars who visited Paris last summer to conduct research that will support a Beauford Delaney exhibition at its facility in Autumn 2025. The exhibition will feature the Beauford Delaney Papers, which the libraries obtained in 2022 and made available to researchers in January 2024.

WIF eagerly supported this research through the Entrée to Black Paris Cultural Awareness Program, providing two guided walking tours, a visit to Beauford’s gravesite, and several hours of consulting as part of its intention to move Beauford Delaney to the forefront of its activities as the 10th anniversary of the Beauford Delaney: Resonance of Form and Vibration of Color exhibition approaches.

Stack granted WIF an interview to share her perspective on these activities from the vantage point of her education and research as a cultural geographer.

Katrina Stack

WIF: What stimulated your interest in geography?

K. Stack: My Master of Science in Historic Preservation was housed in a Geography and Geology Department at Eastern Michigan University, and my advisor there, Dr. Matthew Cook, taught a course on “geographies of memory.” We looked at memorials and monuments and street names and museums and considered the way our everyday landscape influences the memory of the past.

I loved the way that it seemed to make the past more present through considering not only the construction of our landscape, but the contemporary engagement with it. To me, geography took aspects I loved about learning about history and found a way to make them very present. Because it is so interdisciplinary, it allows opportunities to study many things with different methods, and also provides space for great collaboration.

WIF: Please explain what “cultural geography” is and why you are interested in it.

K. Stack: Cultural geography is a sub-field within human geography, studying the relationship between people, their cultures, space and place. Cultural geographers are interested in the spatial patterns of culture and how cultures are presented/represented in the landscape. It’s pretty broad and inclusive in that way, which I find exciting as a researcher.

WIF: What inspired your interest in looking at the African-American freedom struggle from this perspective?

K. Stack: I am lucky that I have been around some amazing scholars who bridge geographies of memory and Black geographies. In the first year of my PhD, I assisted Dr. Alderman in researching the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and temporary housing of evicted sharecroppers who registered to vote in “tent cities” in Tennessee and Alabama in the 1960s, which greatly influenced my dissertation research.

I was also assistant director of his NEH summer institute for K-12 educators on the role of geographic mobility in the African-American Freedom Struggle. I took a class on Black geographies with one of my committee members, Dr. LaToya Eaves, and she exposed me to the work of influential scholars like Bobby Wilson, Clyde Woods, and Katherine McKittrick (just to name a few!).

There are dominant narratives of the struggle for racial justice in the US South that emphasize certain aspects of the Civil Rights Movement, and I’m inspired by the idea of elevating and centering the stories lesser known people and places who were incredibly important to the efforts of their local community.

There are so many stories that need to be remembered and told. Geography helps us to work toward that and consider the contemporary impacts as well.

WIF: How did you become involved with the Beauford Delaney Archives, given that it has little to do with geography?

K. Stack: I saw a post on Instagram about the graduate assistant opportunity, and as I read through the description—working with collections, creating exhibits, public programming and a trip to Paris for research—I saw many things that I hoped to gain experience in. I think, at least initially, I viewed it as more of a memory and public history study, rather than geographical.

I had visited the Beck Cultural Exchange Center a few times, so I knew who Beauford Delaney was. I know a lot more about him now and hope to continue to learn!

Beck Cultural Exchange Center

Image courtesy of Rev. Reneé Kesler

WIF: When you visit a place as you conduct your research, what do you look for?

K. Stack: I look for the whole picture, the “assemblage” of the space, if you will. All its parts, including myself, and others in the space. I try not to narrow myself down on looking for particular things because I have found that could mean overlooking things that don’t seem important in the moment.

I look for connections, but I truly try to take in as much as I can, whether that be visiting more places or taking dozens if not hundreds of photos of scans of documents on my phone. I find that some of my best research opportunities have come from serendipitous encounters, places that weren’t on my planned itinerary. I am hopeful that maybe I’ll have some of that in Paris. I’d say the odds might be in my favor—it seems like there is always something unexpected when it comes to learning more about Beauford Delaney.

WIF: How do you account for changes in geography over time as you conduct research?

K. Stack: I think all changes, whether geographic or spatial or not, require us to be flexible in where we look for information and how we then interpret it. This question connects well to a lot of the big questions I’ve been challenged with in my research: what do we do when places that are important to us, communities we work with, or to history generally are no longer there in their material form? I think those changes and, at times, absences in place can speak loudly in our understanding of space and place.

Betsey B. Creekmore Special Collections and University Archives

University of Tennessee, Knoxville

© Estate of Beauford Delaney

by permission of Derek L. Spratley, Esquire,

Court-Appointed Administrator

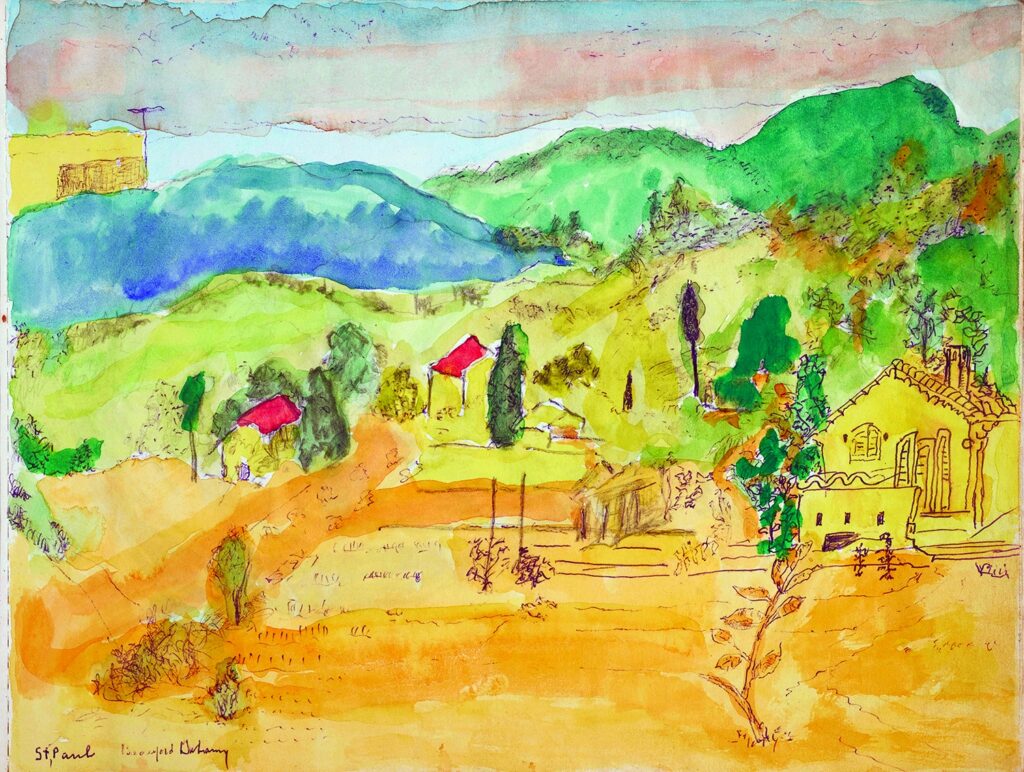

WIF: Will you travel to other places in France to follow in Beauford’s footsteps – places like Solliès-Toucas and Saint-Paul-de-Vence? Do you plan to go to Boston and NYC to explore Beauford’s “places” as you have done in Paris?

K. Stack: We focused on Paris last summer, but certainly other places Beauford traveled and stayed are influential in considering how he saw and understood the world. I see myself moving forward with research on Delaney with even more dedication once I finish my dissertation, which I hope will involve some more of that travel to bring everything together. I believe there is an upcoming meeting of the American Association of Geographers in New York City, and “Delaney places” will be on my list while I am there.

WIF: What will you do with the information you gather on these explorations?

K. Stack: In addition to the February 2025 GeoSym conference and the Autumn 2025 exhibit highlighting the Beauford Delaney papers at Hodges Library at the University of Tennessee, I hope to produce at least one or two academic publications related to this research. I have a running list of ideas that this work has inspired.

I am also very passionate about making my work accessible to the public. So, I have thought about possibly publishing an article on a platform like the Conversation or making educational material that teachers can use in their classrooms. The more I study the collection and learn about Delaney, the more ideas I have — so who knows what can come of this!